In my search for a different culture and an extended summer, I packed my hiking gear and flew to Bali in Indonesia with a one-way ticket at the beginning of May. Together with my partner, Nikola, we spent three months exploring the islands of Bali, Lombok, and Java. We quickly realized that in this jungle and traffic-dense country, the concept of a walking culture is almost non-existent. Most trails are reserved for organized volcano climbs, where local guides and agencies are a necessity. While we traveled together for much of the trip, I decided to face the challenge of Mount Rinjani alone.

View on Mt Rinjani from the Gili islands

Mount Rinjani, an active stratovolcano and the second-highest peak in Indonesia, is a breathtaking part of the Pacific Ring of Fire. Unlike the more tourist-friendly Mt. Batur in Bali, Rinjani is a grand and solemn mountain. For the local people, who are predominantly Muslim, volcanoes are considered holy places—where their gods reside. It’s a place for ceremony and prayer, especially after the big festival of Ramadan. Many believe that at some point in their lives, everyone must make the pilgrimage to Rinjani’s summit. I was fortunate to join a group with my local hostel manager, making his very first ascent, a humbling reminder that even for those who live on the island, this is an awe-inspiring and formidable challenge.

The Unsung Heroes of the Climb

The organized climb, which included a guide and three porters, cost around 130 Euros. I quickly understood why their service was non-negotiable. It would have been nearly impossible for us to navigate the trail alone, as there is very little signage. More importantly, it would have been impossible to carry the necessary gear for a three-day trek on a path that is relentlessly steep.

Preparations before the drive to the Sembalum start point

Our porters were men of superhuman strength. Visibly lean and muscular, they would run ahead of us in flip-flops, carrying massive baskets filled with our food, water, and tents. Each basket weighed around 35 kilograms and was balanced on one shoulder. Some of them have climbed this mountain over 600 times. Their choice of footwear was not a sign of poverty, but a matter of safety; they told me that flip-flops, or even going barefoot, provided better grip and stability on the rocky terrain, since the porters don’t go to the summit but from one camp to another. Watching them work with a smile on their faces while enduring such a burden was a powerful lesson in the value of gratitude. They were happy we had come to their island and were grateful for our business; their kindness was something I felt compelled to reciprocate.

First day climb and the porter

The Sembalum Crater Rim Camp (2,640m)

Day one was an introduction to the trail’s relentless nature. We began our trek at 1,090m through savannas and rainforest, the path weaving through thick fog and past grazing cows. With four rest stops along the way, it took us around seven hours to climb up to the Sembalum Crater Rim Camp. The porters had already arrived, and our dinner was being prepared in their cooking tent. The breathtaking view of the crater lake far below was our reward, and we watched the sunset paint the sky from the entrance of our tents. A few bold monkeys lingered nearby, used to the endless stream of tourists and the food and trash they leave behind, hoping to steal something from us.

After dinner, the temperature dropped quickly, making sleep a challenge. I shivered in my sleeping bag, anticipating the long night ahead before our pre-dawn start. The guide’s instructions for the summit climb were simple: a steep path, a flat part, and then a very steep section with volcanic sand. We had four hours to climb 1,100 meters if we wanted to see the sunrise. The summit alarm went off at 1 a.m., and we began our ascent.

Our tents on the Sembalum Crater Rim Camp and the monkey

“Two Steps Up, One Step Down”

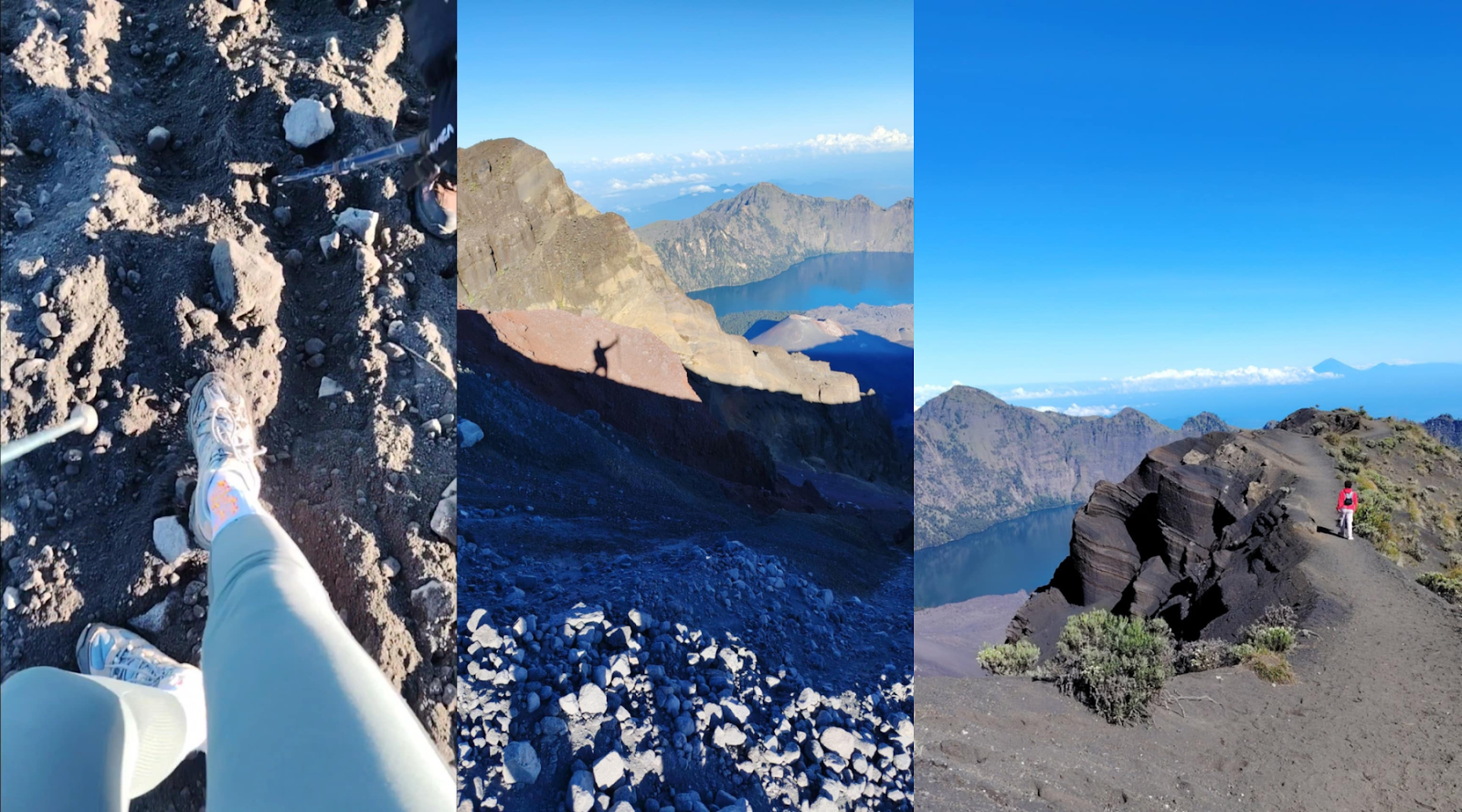

The night was pitch-black, with a magnificent starry sky, and the only light came from the headlamps we had all rented. My group consisted of 8 people from all around the world, but I believe around 200 people were attempting to climb the summit that morning. The first segment of the climb proved to be much more difficult than the guide had suggested. My feet sank into the deep volcanic sand with every step, making forward progress feel like a Sisyphean task. The mantra of the climb became, “two steps up, one step down.” We were surrounded by large rocks, which provided some much-needed leverage on the steep, narrow path. I couldn’t help but notice many tourists who were utterly unprepared for the climb, attempting it in regular city sneakers. After reaching the second segment, my body began to warm up, and I fell into my own rhythm —a pace that was slower but steadier. The path was definitely not ”flat” but also steep, which made me frustrated and scared since I had calculated the time I would have for my body to rest before the summit. At that point, I realized the information we receive is not complete and accurate.

Climbing the summit in the middle of the night to reach the sunrise time

The third and final segment was the hardest climb I have ever done. The last 200 meters of the volcano’s peak were covered in small, loose volcanic sand. There was nothing to hold on to but your own body strength and hiking sticks. The “two steps up, one step down” phenomenon became a grueling mental practice. It felt like I was working incredibly hard without making any progress. At one point, I turned back and saw a long line of headlamps stretching far behind me. I knew many of them would not reach the summit in time for sunrise, or perhaps not at all. That moment of comparison made me feel both grateful and proud, and it gave me the strength to push on, even as tears of exhaustion welled in my eyes. The last 100 meters felt infinite. I realized that the only thing pushing me forward was an internal rush to witness the sunrise.

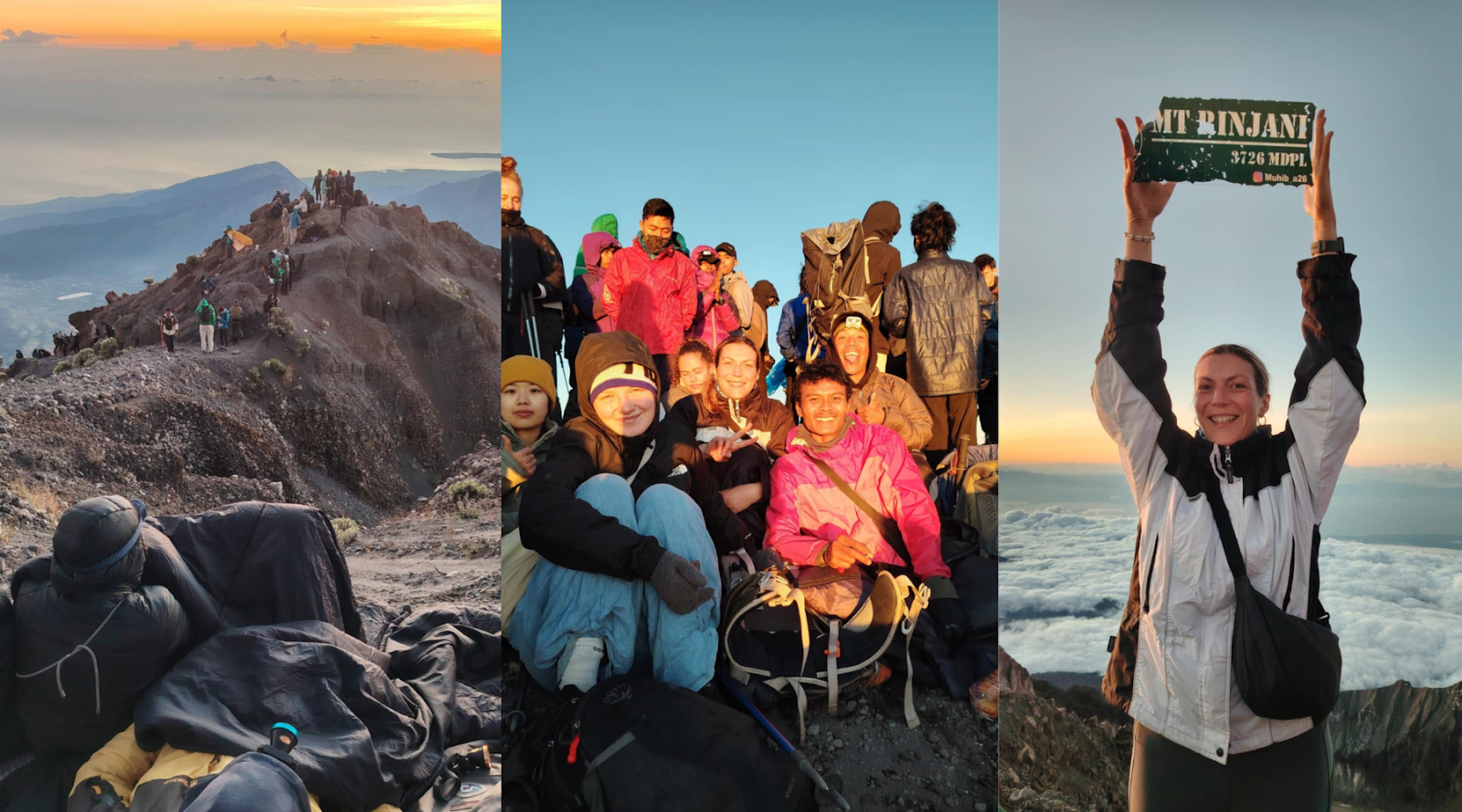

Waiting for the sunrise on the top

When I finally reached the summit at 3,726m, the feeling was a familiar mix of exhaustion and triumph. I found a spot next to my group, wrapped myself in my sleeping bag, and waited for the sun to rise. I knew this was likely a once-in-a-lifetime experience, so I savored every moment. The view was spectacular: the crater lake glowing with volcanic colors, the infinite expanse of the Indian Ocean, and the snaking path that lay both behind and ahead of us.

Our group photo and proof that we made it!

The Descent and the Torean Route

Our guide had promised the descent would be “easy peasy,” and he told us to expect it to take around two hours. For me, it was a grueling four-hour struggle. I had to consciously adjust the angle of my feet to stop the constant sliding, a maneuver that put a tremendous strain on my knees. As other hikers ran, slid on their backsides, or glided with ease, I followed my own slow and painful pace. At one point, I was completely alone on the crater rim. I closed my eyes, taking in the profound silence. When I opened them, I was unsure which way to go, but a small boy appeared and pointed the way, then stayed close to me, a silent guardian for the rest of my descent.

The volcanic sand is everywhere above the Sembalum Crater Rim Camp

Back at the base camp, the group was already packed and ready to continue. Three men, one of them was also my hostel manager, had already given up and started hiking back to the starting point. With no time to rest my aching knees, I ate breakfast, changed clothes, and began the next phase of our journey: a nine-hour trek all the way down to a new camp.

The Torean route was unforgiving. The path was made of jagged, rocky steps with no fences or handholds to aid navigation. As a European climber, I was accustomed to well-organized and safe trails, but this was a wild and untamed path. About an hour into the descent, our guide angrily approached me, telling me I was slowing down the group and that we wouldn’t reach the campsite before nightfall. He suggested I turn back. I quickly calculated that his plan would result in me hiking the same distance alone, and I refused to do so. The rest of the group supported my decision, accepting that we might walk in the dark. A kind man from the group even offered to carry my backpack for a while, a gesture that gave me a much-needed boost.

The beauty and difficulty of the Torean route

My knees were screaming in pain with every step, but I was determined to finish what I had started. The group dynamic shifted, and I discovered I wasn’t the only one struggling. The other girls in the group were also exhausted, and we became a team of solidarity. As we walked through the jungle, we were rewarded with magnificent views of waterfalls from above, a powerful reminder of nature’s raw energy. Just before reaching our camp, we stopped at a natural hot spring, where we sank into the basin of bubbling water to soothe our tired muscles. That night, we sat around the campfire in a comfortable silence under the Milky Way cap, exhausted but deeply thankful for having finished a long and challenging day. We all slept like babies, our bodies finally giving in to the fatigue and our minds at peace.

Resting in the natural hot spring

Our second camp next to the river, looking onto our previous Sembalum camp; and the third day path

The End and The Lesson

Our third and final day began with breakfast and a visit to a rare source of drinkable water. The path back through the jungle was easier, taking about seven hours. We crossed a “monkey forest,” where our guides instructed us to look down and avoid eye contact to prevent the monkeys from attacking. We happily finished our trail in the Torean village, gave the extra tips to porters, said our goodbyes, and went our separate ways.

I was recovering mentally and physically for the next 4 days in Senaru village, where I even got the ‘Rinjani recovery’ infusion from the local doctor. I was sure my body was well-prepared for this climb, but it ultimately exceeded my capabilities. I later spoke with some locals in the central village, where most of the Rinjani agencies are located. I shared my experience with them, explaining how some of the information about the climb had been missing. They smiled and said that if they told the whole truth, “nobody would pay to do it.”

This climb changed my perspective on Indonesia. It helped me see it not just as a beautiful country, but as a complex tapestry of wild nature, a struggling economy, and people who depend on tourism to sustain their livelihoods. Over the next two months, I learned about the dangers posed by the country’s growing mass tourism and the weak and ineffective rescue services available on volcanoes and other adventure-tourism locations. While I am incredibly grateful for this transformative experience that has profoundly changed my perception of the world, the honesty of the locals has made me realize that I will seek future hiking trails elsewhere.

A group photo with the guide in the Torean village before we said goodbye and went our separate ways ☺

However, I will definitely return to Indonesia, as it has become a place of unpredictability and a profound connection with nature, in areas that finally find you when you least expect them. Rinjani helped me to understand it and surrender.

The total route from the Sembalum starting point to the Torean end point is approximately 28 kilometers, completed over 3 days with more than 30 hours of walking, with a total elevation gain of over 2,500 meters and a descent of more than 3,100 meters.