Hvar Hike is an article about an experience with insider guidelines on multiple ways to hike Hvar mountain, including several recent climbs as well as routes walked in past years. If anyone decides to explore the island on foot, this article can give a broader picture of the possibilities held by its ancient spine. For this purpose, I created a map with existing walking routes connecting northern and southern locations across the mountain.

Hvar Hike map

St Nikola (626 m): Starting from Svirče

Our most recent hike was a symbolic one, on St Nicholas’ Day, when Nikola and I decided to visit Hvar’s highest peak — St Nikola (626 m). It felt natural rather than planned, one of those walks that happen because the day asks for it. St Nikola is considered the third-highest peak of Croatia’s islands, with astonishing views over the central Dalmatian archipelago. The peak is part of Hvar mountain — a rocky reef stretching along the island’s southern side, shaping the character of the entire island. This ridge is not just a line in space; it defines climate, movement, labour, and imagination.

View from the top of Hvar on Šćedro and Korčula

At the top stands a small chapel of St Nicholas, mentioned as early as 1495. Its existence reminds me of the circumstances of past islanders, who seasonally migrated from the north to the south side — for farming, but also to transport water to the drier, harsher slopes. Walking here always feels like stepping into a rhythm much older than hiking.

There are several paths leading to St Nikola. This year, we chose the one starting from Svirče, which is less steep than the route from Sv. Nedjelja on the south side. Both take around two hours to reach the top, but experientially they are very different. Ideally, they should be connected to experience the full diversity of the landscape. That requires transport at the other end, which was logistically complicated this time, so we decided to start and finish in Svirče.

The walk begins along a beautiful gravel road, framed by old dry-stone walls, with olive groves and vineyards stretching behind them. Svirče is known for high-quality wine and olive oil, and most locals are still deeply engaged in cultivating vines and olive trees. This first section always slows my pace — not because it is hard, but because it feels dense with lived time.

Trail start from Svirče and beautiful horse enjoying morning sun

After about 200 metres of ascent, the landscape changes. Gluhi bor, the Dalmatian black pine (Pinus nigra ssp. dalmatica), begins to appear, with its twisted trunks and almost irrational crowns. Some of these trees have been growing here since the last Ice Age — over 10,000 years ago. Once part of a much wider forest, these pines survived only in locations where they were not frozen out, developing separately from other European black pine varieties. Today, they exist only in a few pockets: on Brač, Hvar, Korčula, the Pelješac peninsula, and high on Mt Biokovo. On Hvar, they grow as high as possible, along the ridge and the northern slopes of St Nikola.

Dalmatian black pine (gluhi bor)

Poljica Plateau

After about an hour of gentle climbing, we reached the Poljica plateau. From here, other islands start to appear, and the terrain opens into a vast surface covered with stone walls. Every time I come here, I am reminded of the mysterious energy this island holds. Hvar’s landscape often leaves me breathless — not because of altitude, but because my imagination starts to connect the stories I have heard and read with the landscape opening in front of my eyes. Stories and myths surface easily: people migrating to the highest areas in search of refuge, a cyclops who might have lived somewhere here, black magic that removed part of the mountain, and other narratives still waiting to be discovered. About ten years ago, I heard about a newly built labyrinth somewhere on the plateau, but I never managed to find it. The fact that it remains invisible only strengthens my affection for a few quietly mysterious islanders.

From the plateau, the climb continues across harsh karst terrain, along a path that leads onto a protruding ridge. Winter bushes shimmer in silver and gold, and medicinal herbs release their scent underfoot. There are a few weekend houses where locals grow lavender, immortelle, grapevine, or other crops suited to this high-altitude terrain. Still, it feels like a long, open space, defined mainly by pines and the ridge itself, which also serves as shelter from southern winds.

Autumn flora on the ridge

While walking along the ridge, we felt the light south wind for the first time. Winter rewarded us with clear weather and a strong sun that kept us warm the entire way. After reaching the top, we sat next to the southern wall of the chapel, eating fresh winter mandarins and clementines, soaking in the morning view. The horizon unfolded slowly: Pelješac and Korčula to the far east, Šćedro silently sleeping right below us, Sušac dissolving into fog in the distance, Pločica and Lukavci bathing in reflected light, great Vis to the west, and the Pakleni Islands hiding behind the steep southern rocks of the reef. Directly below lay Sv. Nedjelja, an isolated summer settlement that requires a long drive to reach. Starting from there would create a completely different scenario — one I have walked many times, usually on the way to another highly energetic and mysterious place.

The South Side

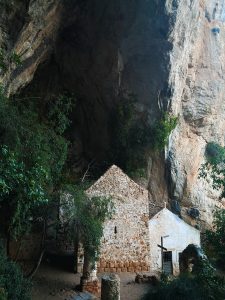

The Cave of Sv. Nedjelja, with its abandoned monastery and chapel, was built by Augustinian monks in the 15th century and inhabited until the 18th. Today, only bats live there, though I often notice traces of someone who keeps returning, carefully rebuilding stone-balancing sculptures. The southern cliffs are also home to free climbers, drawn by the perfect rock terrain, most often during the summer months. The slopes are steep, with narrow field paths passing through always-sunny vineyards of Plavac Mali and other local grape varieties that give Hvar wines their depth and strength.The climb from Sv. Nedjelja to the cave takes around 30 minutes of intense ascent. I don’t recommend attempting it in July or August — unless your goal is to resemble a red crab with a dangerously high heart rate. Other starting points, with existing ancient paths among the vineyards, could also be Ivan Dolac or Zavala, both of which are still on my bucket list.

Look onto Sv. Nedjelja and sneak peek from the cave

The Spine

Usually, I hike Hvar’s paths in fragments. Still, I hope that one day I will manage to walk the entire mountain reef, from Humac in the east to Brusje in the west — around 30 kilometres of ridge, stone, and wind. The western part of the island (Brusje, Velo and Malo Grablje) is famous for beautiful lavender fields cultivated before the big fire that, according to some islanders, irreversibly destroyed the last autochthonous Hvar lavender. What remains today are large areas of stone walls shaping what I like to call the island’s fingerprint — thousands of kilometres long.

A few years ago, I joined a two-day pilgrimage hike, passing from Hvar to Stari Grad (18 km), then from Stari Grad to Jelsa (17 km). It was a great opportunity to explore hidden gems and remnants of the past, concealed in the bushes and visible only to “VIP guests” — such as megalithic walls, ritual stone mounds, towers, a doctor’s house, and, of course, many chapels. 🙂

1. Velo Grablje stone walls; 2. Descending to Stari Grad; 3. St Vid church remains above Svirče

Another path I often walk, worth mentioning for anyone who decides to wander deeper into the island, lies about 8 kilometres east of St Nikola, above the village of Pitve. There is an area called Vrotnik — “the doors” — a V-shaped valley above Pitve, whose clouds often foreshadow changes in the central island’s weather due to differences in air pressure. When we are unsure whether a storm is approaching Jelsa, we simply look at Vrotnik and observe its clouds.

After Humac, Pitve is one of the oldest settlements on the island, positioned strategically inland, far from historical sea attacks. The path follows the valley toward the chapel of St Anthony, opening astonishing views to the south over the archipelago and to the north toward Brač and Biokovo. The terrain is a gently steep gravel path, surrounded by rosemary and strawberry trees (planika). In autumn and winter, you won’t stay hungry; in May, the area burts into hundreds of colours and early-summer scents.

1. Vrotnik valley; 2. St. Anthony chapel; 3. planika for lunch

I hope I managed to give you a glimpse of how island culture overlaps with today’s sports activities. In the next article, I will write more about biking — Hvar Bike. 🙂 If you decide to explore the island on foot, wander its ridges, valleys, and forgotten paths, feel free to let me know. I am always happy to walk Hvar together — slowly, from the inside.

Svirče – Sv. Nikola – Svirče

14km – 4h – elevation 547m

Ivan Dolac – Sv. Nikola – Sv. Nedjelja

10km – 3.30h – elevation 600m

Sv. Nedjelja – Sv. Nikola

4km – 1.15h – elevation 510m

Beautiful and very useful! Hvar has been on my planning map for a long time. Now I have an additional reason to visit! Thank you, Josipa!